Where would your mind wander were you to hear the word "worms" wailed wildly like some roar for war? After turning round and asking "wherefore art thou weirdo?" you may well cast your thoughts toward the earthworm. And who could blame you? Earthworms are the classic worm, the one we all know, the one we most often come across. Or maybe you would go for the rather more macabre leech? Get some blood sucking and catharsis in there. And who could blame you? At least it's better than some of the other things worms can get up to. Both the leech and the earthworm are annelids, or segmented worms. So are ragworms, tube worms and polychaetes. Annelids can be found everywhere from the deep sea to freshwater ponds to damp soil and leaf litter. Each segment is identical to each other, even containing the same internal organs. They can be predators, detritivores, filter feeders and more besides. They might even secrete a tough tube to live in forever. Some segmented worms aren't even segmented! Today we'll look at tube creatures that have a head and... would you call it a tail? Some are closely related to annelids. Others are scarcely related at all. It's a very popular shape!  Image via Wikipedia Image via WikipediaI don't want to blind you with science, but flatworms are a sort of worm that's flat. With me so far? The reason for them to be so flat is that they have no respiratory or circulatory systems, no lungs, gills or blood vessels. Instead, oxygen and nutrients have to be absorbed by their cells via diffusion. They also have guts that branch out as much as needed to ensure food reaches all the cells of the body. Most are parasitic. They can be microscopic parasites like some of the flukes or horribly big parasites like tapeworms. Many are internal parasites, residing in the intestines perhaps, while others grip onto the skin of fish and other aquatic animals. Some are not so lazy. There are flatworms that are free-swimming in the sea or free-crawling in rotting wood and decaying leaves. These are usually predators or scavengers. They can also be very pretty and brightly coloured. I doubt the parasitic ones are though. | ||

Image by Vishal Bhave via Flickr Image by Vishal Bhave via FlickrRibbon worms are almost entirely marine, usually spending their time at the bottom of the ocean. Some are half a centimetre long, others can reach over 30 metres (98 ft)! That rivals the blue whale! What on earth?! They're still extremely thin even at that length, so they shouldn't pose any threat to shipping. A good thing too, because these guys are mostly carnivores and armed with a proboscis. This is a long tube at the mouth, like butterflies, except ribbon worms often have a sharp stylet at the end. This lets them stab crustaceans and annelids repeatedly until dead. Some are even poisonous. Others have a sticky proboscis instead. Either way, they can wrap it around their prey and reel into their mouth. That's disgusting, but they have a brain and blood vessels so at least things are looking up in some ways. They don't have a heart though, which might be why they can forgive themselves for eating that way. | ||

Image via Wikipedia Image via WikipediaNow we're getting somewhere! Actually we're going EVERYWHERE, because that's where roundworms, or nematodes, can be found. Mountains, deserts, freshwater or marine. Parasites of animals or plants, carnivorous or herbivorous. Nematodes are doing it all. There are believed to be about 1 million species in total. Perhaps the most important reason for their success is that their skin is a tough, protective cuticle that serves as an exoskeleton. The head is armed with sensory bristles and all sorts of bits and bobs for whatever they eat. Some eat algae, others bacteria, others eat other nematodes. Some can pierce animals or plants and suck out the contents. They can be less than 0.05 mm (0.02 inches) and sometimes over a metre (3.3 feet) long. Apparently, one was found in the placenta of a sperm whale that was 8 metres (26.2 feet) long! Yikes! We have already met the sperm whale. Reading it over again with the thought of an 8 metre long parasitic worm fresh in the mind is... thought provoking. | ||

Image via Wikipedia Image via WikipediaAnother parasite and another proboscis. This worm gets its name from the fact that it has a proboscis armed with rows and rows of hooks. This allows them to pierce the gut wall of their host and hang on as food washes over them. They simply absorb this all across the surface of their body, much like tapeworms. They have no guts of their own any more, so they can't even sympathise with the fish or bird they are intruding on. | ||

Image by Anders Lennver via Flickr Image by Anders Lennver via FlickrHorsehair worms are similar to nematodes in some ways but apparently they aren't closely related. They are usually 5 to 100 centimetres (2 to 39 inches) in length, but some can double this. That would have been absolutely extraordinary before that massive nematode. Anyway, adults are free living in damp and wet areas like puddles and streams. They were often found in watering troughs where people thought they were horse hairs come to life, hence the name. The real explanation is the fact that while adults appreciate the worm equivalent of the wind in their hair and water on their cuticle, the youngsters are parasites of land living insects like cockroaches and grasshoppers. When the time is right, they can manipulate their host and cause it to leap into water and drown. As the insect struggles and desperately asks "but what's my motive?", an improbably and appallingly long adult worm squirms out and swims off like an eel. Away, to better times and bigger crimes. | ||

Image by wildsingapore via Flickr Image by wildsingapore via FlickrThese worms are often considered a kind of marine annelid, even though they aren't segmented. Some species have blood vascular systems like annelids do, others don't. Weird how that can be a choice! They live in burrows and have a tube shaped proboscis, possibly several times longer than the rest of the body, that they project out the top. Bits of food settle on the proboscis for them to eat. | ||

Image via Wikipedia Image via WikipediaStop sniggering, it was bound to happen eventually! Penis worms are another marine mud dwelling worm, reaching lengths between 0.5 and 20 centimetres (0.2 and 7.9 inches). No comment. They have a chitinous cuticle (like an insect exoskeleton) that has to be moulted as they grow. They also have an eversible pharynx, which is like a throat that can be turned inside out and pushed out of the mouth. Lovely. This is armed with teeth for capturing and eating slow-moving worms and the like. It's thought that these were once major predators during the Cambrian period. How times change. | ||

Image by zodama2003 via Flickr Image by zodama2003 via FlickrYet another marine burrower, but this time not all of them can be found in mud. Some peanut worms occupy disused snail shells and some can even bore into chalky rock. Sounds like some good protection there, so you can understand that they would seldom leave it. Instead, they have a tiny mouth surrounded by a couple dozen small tentacles, all at the end of a long, tube structure called an introvert. So while the main body is fully hidden and protected, this hose pipe with a gob at the end moves around, seeking out food in the water or substrate. It can also be retracted into the body if need be, or regrown if it gets chopped off. The peanut worm can also retract the other end until it looks a bit like a peanut kernel. They range between 2 to 720 millimetres (0.079 to 28 in) in length. | ||

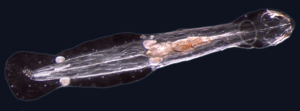

Image via Wikipedia Image via WikipediaA little different, this one. At just 2 to 120 millimetres (0.079 to 4.7 in), arrow worms range between small and tiny, but don't let that fool you. They can be found throughout the world's seas, from the surface to the bottom, from the poles to the equator and even little pools when the tide goes out. They are covered in a tough, flexible cuticle and have a kind of fin at the tail and two more on the body. Undulations allow them to swim like an eel in short bursts, but they usually drift as plankton. They have bristles all about them for sensing their surroundings and, amazingly enough, compound eyes. Well done! Then there are the 4 to 14 hooked spines at the sides of the head. These are used for grasping tiny, planktonic prey in a way that is probably really dramatic and impressive. It's a whole other world... | ||

Image via Wikipedia Image via WikipediaYou only have to look at an acorn worm to know why it's considered one of the most advanced of their brethren. That isn't actually true is it. Oh well. But get this, acorn worms have a heart! It's weird because while it pumps, it's completely closed and doesn't have holes or tubes coming off to take blood around. It also works as a kidney. Err... right. Even if the heart doesn't seem to care much, the acorn worm is the proud possessor of 2 long, blood vessels, woo! They also have gills for breathing, not unlike fish. This is great! So what does the acorn worm do with this incredible array of fancy new equipment? It burrows into the mud. Great. Another marine burrower. Some also eat that mud like an earthworm, while others are suspension feeders, using tiny hairs to draw drifting food toward the mouth. Length ranges between 9 centimetres and 1.5 metres (3.5 inches and 4.9 ft) and they can be found from the sea shore to impressive depths of 3,050 metres (10,000 feet). They are closely related to echinoderms, like starfish and sea cucumbers. Eating mud isn't particularly taboo in that company. ..... Circus of the Spineless #59, hosted at The Shell and Mantle. |

Sunday, 30 January 2011

A Wonderful/Worrisome World of Worms

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

Your blog is a marvelous look at the less "beautiful" plants and animals in our world. I feel lucky to have come across it.

Real Monstrosities is Nature Site of the Week at Nature Center Magazine.

Emma Springfield

Pretty darned interesting I'd have to say. I was most intrigued by the hairworms and their impacts on insects. So much for suicide prevention amongst grasshoppers! This was fun!

@Emma: Oh wow! Thank you. Kinda makes ME feel lucky you came across it!

@bill: Thanks a lot bill! And yes, it looks like grasshoppers need a number to call for when they feel strange, suicidal urges.

Post a Comment